Published on January 21, 2026 · 9 min read

Key takeaways

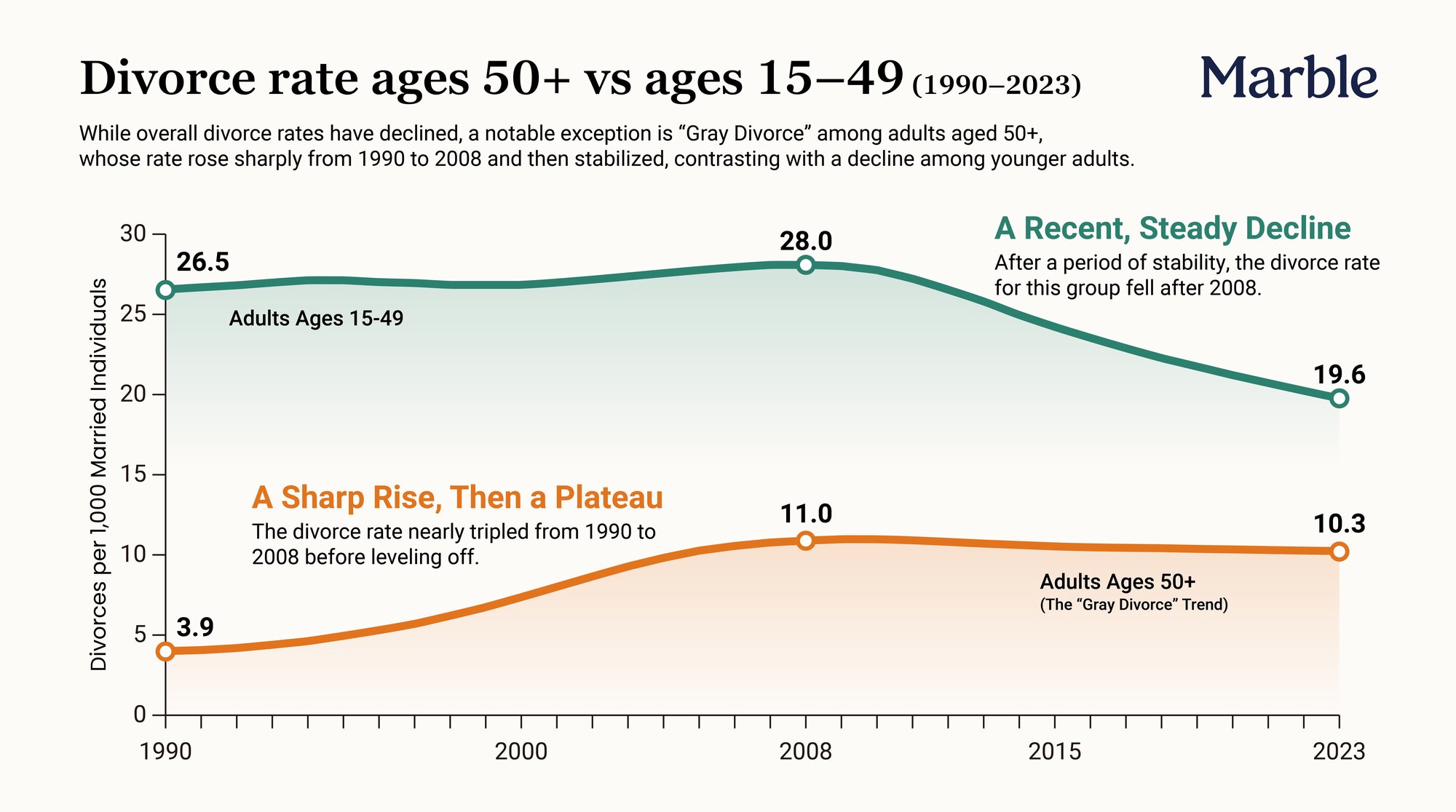

- Gray divorce rose from 3.9 divorces per 1,000 married women ages 50+ in 1990 to 11.0 in 2008, and remained relatively stable at 10.3 in 2023\.

- Divorce trends diverge sharply by age. For example, the refined divorce rate for women 65+ rose from 1.4 (1990) to 6.7 (2023) per 1,000 married women.

- Gray divorce often follows long marriages. In 2022, the median marriage duration at the time of a first gray divorce was 29 years, versus 18 years for those divorcing from a remarriage.

- Later-life divorce often involves remarriage histories. In 2022, about 55% of adults experiencing a gray divorce were divorcing from a first marriage, while the remaining share were divorcing from later marriages.

- The stakes are frequently financial and administrative. Divorce timing is linked to different economic profiles in older age, and later-life divorce can affect Social Security, health coverage, and taxes.

What “gray divorce” means, and what it does not

Gray divorce refers to divorce among adults aged 50 and older, commonly measured as a rate per 1,000 married women aged 50 and older. It does not mean divorce is increasing every year among older adults. The more accurate read is that gray divorce climbed quickly in the 1990s and 2000s, then leveled off at a sustained, elevated level through 2023\.

It also does not mean most divorces happen after 50\. What it does mean is that later-life divorce now represents a larger share of overall divorce than it did a generation ago, partly because divorce has declined among younger adults and because the older population is larger.

A simple way to think about it is this: the overall divorce “temperature” has cooled, but later-life divorce has stayed warm enough to remain a defining feature of modern family change.

The trendline: A rapid rise, then a sustained plateau

If you want the clearest “story in three numbers,” Pew’s synthesis lays it out:

- 1990: 3.9 divorces per 1,000 married women ages 50+

- 2008: 11.0

- 2023: 10.3

The key nuance is what happened in parallel for younger adults. Pew notes that divorce rates among individuals aged 15 to 49 remained relatively stable from 1990 to 2008, then declined between 2008 and 2023\. This is why gray divorce stands out, even as overall divorce rates are down.

Who is driving it: Later-life divorce rises most at older ages

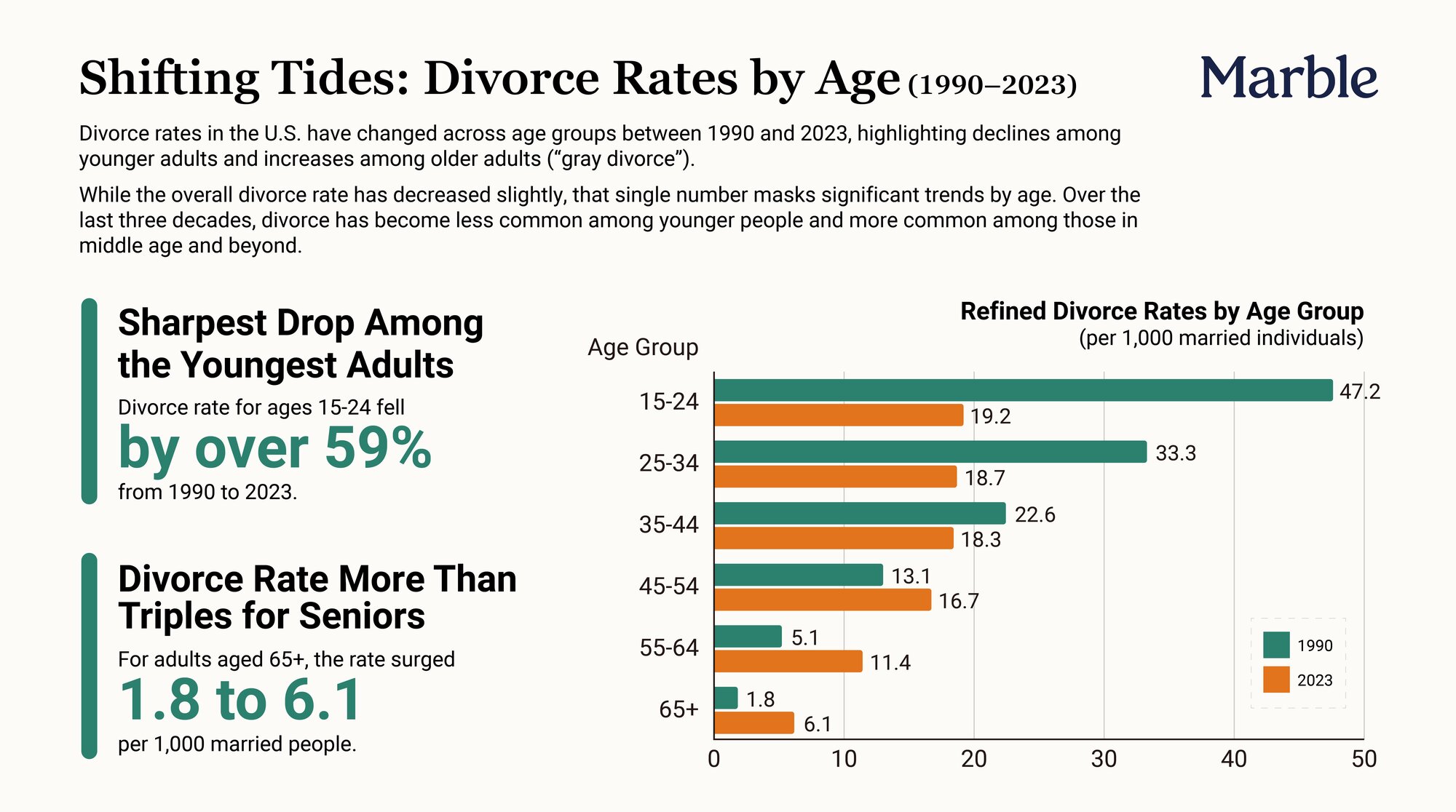

“Gray divorce” is the headline, but the deeper story is age divergence, especially at the oldest ages.

NCFMR’s age-variation profile shows that between 1990 and 2023, refined divorce rates declined for younger adults and increased for older adults. The sharpest decrease was observed among individuals aged 15–24, while older age groups saw sustained increases. For women aged 65 and above, the divorce rate rose from 1.4 (1990) to 6.7 (2023) per 1,000 married women.

This helps explain why national averages can mislead. A single national divorce number is the sum of very different age-specific patterns that have moved in opposite directions over time. A steady gray-divorce plateau can exist at the same time younger divorce is falling, because different age groups are on different trajectories.

Marriage duration: Gray divorce often means untangling decades

Later-life divorce is strongly associated with long marriage duration, but duration differs sharply depending on whether it is a first divorce or a divorce from a remarriage.

NCFMR’s marriage-duration profile (2022 ACS) reports:

- Median duration at first gray divorce: 29 years

- Median duration at gray divorce in a remarriage: 18 years

The distribution also shows that “short marriages” are far more common in remarriages than in first marriages at older ages. Among the first gray divorces, 3.6% occurred within five years of marriage. Among gray divorces from a second or higher-order marriage, 15.3% occurred within five years.

This is where the storyline shifts from trendlines to lived reality. A 29-year marriage often means shared housing decisions, shared retirement contributions, and shared expectations about caregiving, adult children, and future roles. A later remarriage may be shorter, but it can still have significant financial consequences, particularly when retirement is near or underway.

Multiple gray divorces and remarriage histories

Gray divorce is sometimes one transition within a longer marital history, not a single one-time event.

In 2022, NCFMR estimates that about 55% of adults experiencing a gray divorce were divorcing from a first marriage. The remaining share were divorcing from later marriages, including second and third-plus marriages. These patterns matter because later marriages often come with different family structures, including adult children from prior relationships and long-standing obligations that affect financial planning and household decisions.

NCFMR also tracks “multiple gray divorces,” showing that a smaller share of people experience two or more gray divorces, with variation by gender and by race and ethnicity. This is part of why later-life divorce is often linked to blended families, repartnering, and more complex long-term planning.

Geography: What we can say with confidence about where gray divorce is higher

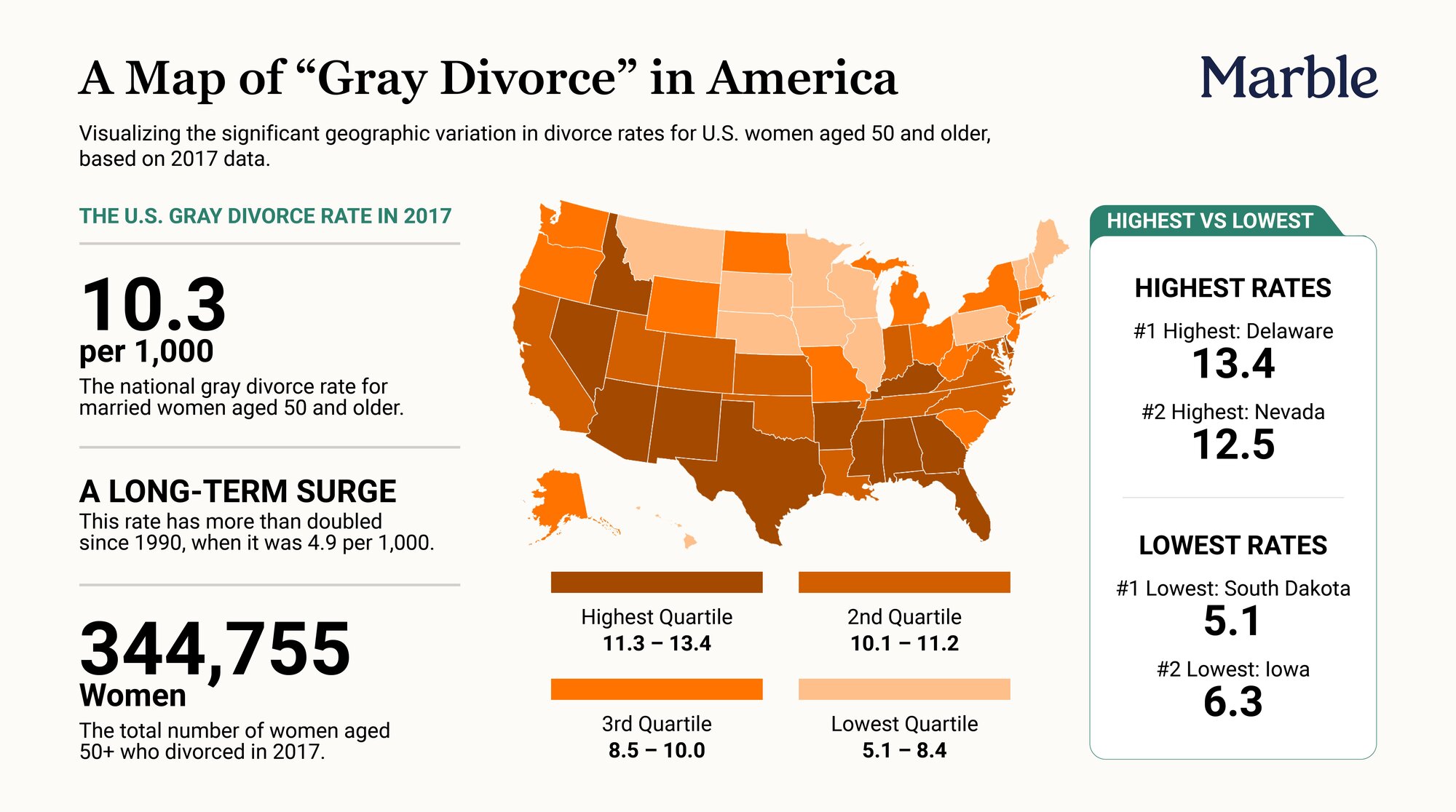

To discuss geography responsibly, you need a source designed for state comparison. NCFMR’s geographic variation profile defines the gray divorce rate as divorces per 1,000 married women aged 50+ and provides a state-comparable snapshot.

Nationally, the gray divorce rate more than doubled between 1990 (4.9%) and 2008 (10.7%), then eased slightly to 10.3% by 2017\. In 2017, the profile estimated that 344,755 women aged 50 and older were divorced.

State variation is meaningful even when the national rate is steady. The profile highlights:

- Delaware has one of the highest (over 13 per 1,000 married women 50+)

- South Dakota is among the lowest (about 5 per 1,000 married women 50+)

- The highest quartile at 11.4+, and the lowest quartile under 8.5

Because these are ACS-based estimates, the best use is to describe patterns and relative differences, rather than treating them as real-time court filing counts. Still, geography matters because it shapes what feels “normal” in a community and what local resources are more commonly used.

The money side of gray divorce: Why timing changes the outcome

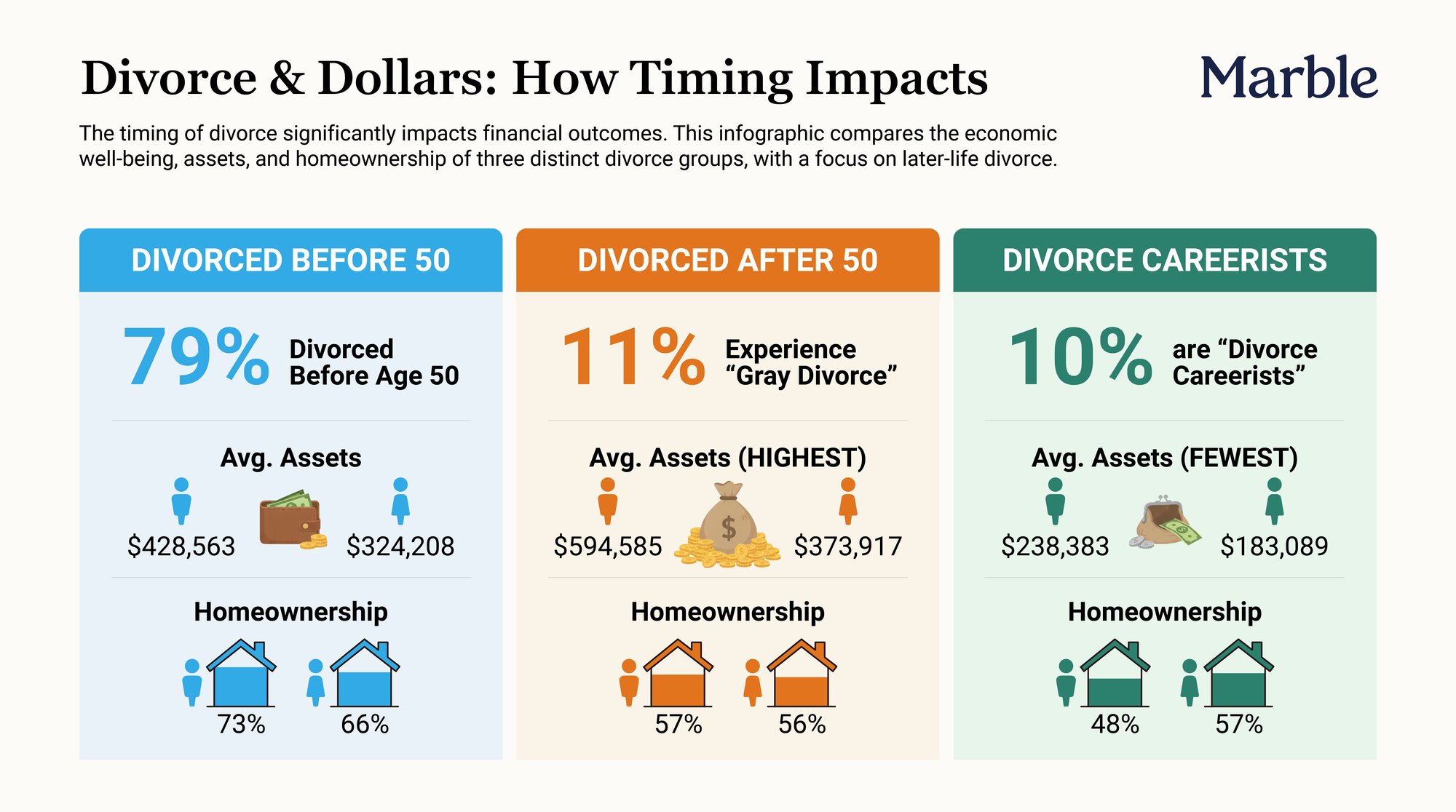

Gray divorce is often described as emotionally challenging, but the data also show that it is financially significant, and timing matters.

NCFMR’s economic well-being profile (based on the Health and Retirement Study) separates older adults who have divorced into three groups: those who divorced before age 50 (79%), those who divorced after age 50 (11%), and “divorce careerists” who divorced both before and after 50 (10%).

The profile reveals that economic well-being can vary substantially across these groups, including disparities in assets and homeownership. In general, divorcees have notably weaker balance sheets than those who have divorced only once in a given life stage. A practical interpretation is that repeated household splits can reduce the ability to rebuild wealth over time, while later divorce can hit at a stage when retirement planning is less flexible.

At the policy level, GAO has also highlighted that older women can face retirement security challenges and that life events such as divorce can contribute to financial vulnerability in later life.

Benefits and paperwork: Three systems people miss

Even in amicable gray divorces, people often underestimate the number of systems a divorce affects. Three of the most common blind spots are Social Security, health coverage, and taxes.

Social Security (divorced spouse and survivor pathways)

Federal rules allow some divorced spouses to qualify for benefits based on an ex-spouse’s earnings record if requirements are met, including rules tied to marriage length and marital status. Survivor benefit rules can also apply to divorced spouses in certain circumstances.

Health coverage (COBRA after divorce)

If you were on a spouse’s employer-sponsored plan, divorce can be a qualifying event that triggers COBRA continuation coverage in many cases. DOL guidance explains the continuation framework and cost structure.

Taxes (filing status and related rules)

Divorce changes the filing status rules and can affect the responsibility associated with prior joint returns. IRS Publication 504 outlines federal tax rules for divorced or separated individuals.

This is where gray divorce often differs from earlier divorce. You may be managing retirement accounts, long-standing insurance arrangements, and a decades-long financial history. A checklist approach can help you avoid avoidable surprises and reduce downstream clean-up work.

The bigger demographic context: why gray divorce shows up more now

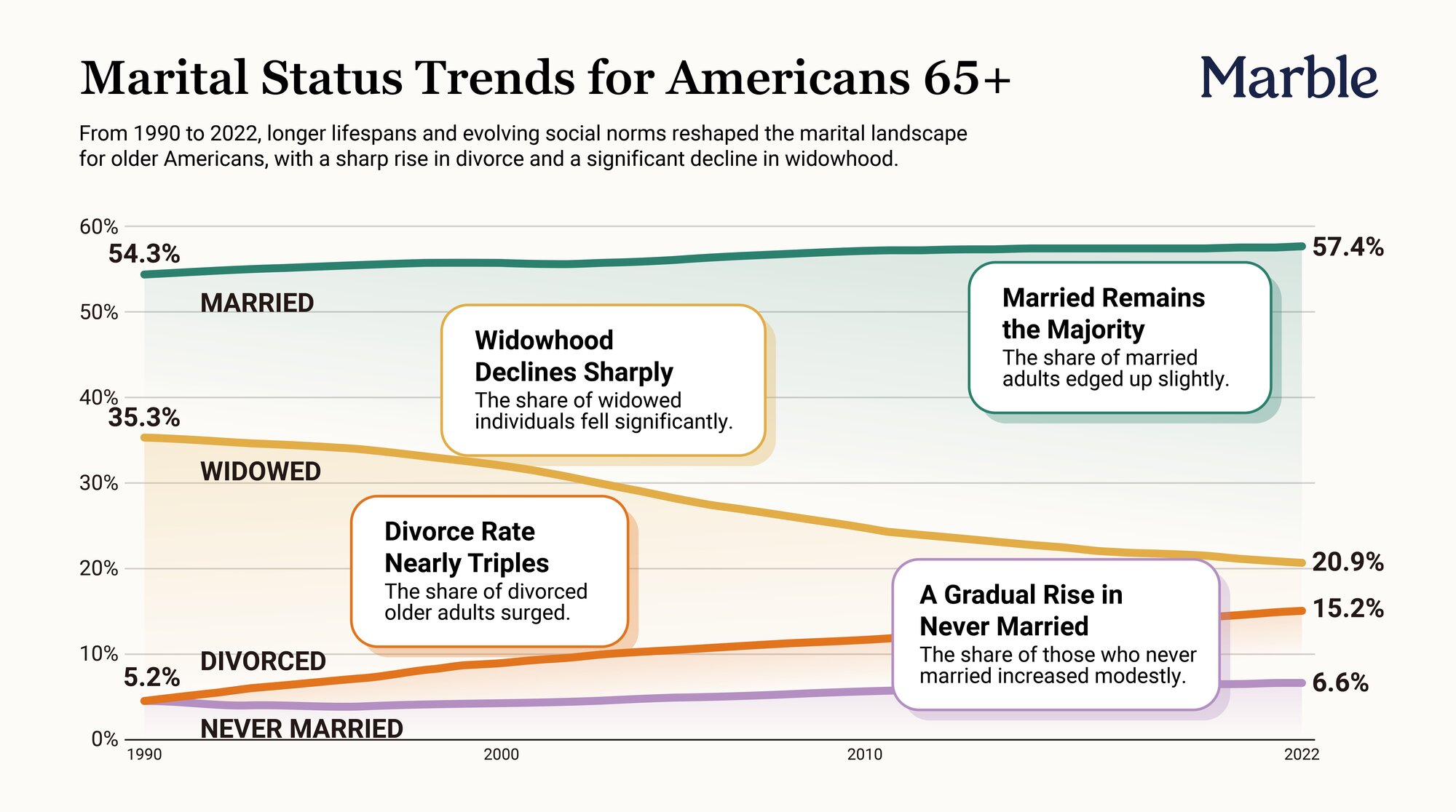

Gray divorce is unfolding alongside a broader reshaping of later-life marital status. In 2022, NCFMR reports that among adults 65+, the share who were divorced rose to 15.2%, nearly triple the 1990 level (5.2%). Over the same period, the rate of widowhood fell substantially (from 35.3% to 20.9%), while the share of married individuals edged up (from 54.3% to 57.4%).

This matters because when a larger share of older adults are divorced, and fewer are widowed, later-life partnership and legal dissolution become more common features of the older-adult landscape. It is also consistent with broader research that describes gray divorce as a multi-decade demographic shift in U.S. family patterns.

Conclusion

Gray divorce is no longer a niche phenomenon; it has become a widespread trend. The rate rose sharply from 1990 to 2008 and has remained at a higher, sustained level through 2023\. At the same time, divorce trends have diverged by age, with older adults, including women 65+, experiencing rising divorce rates over the long run.

What makes gray divorce distinct is the context. It is often associated with long marriages, remarriage histories, and financial systems established over decades. That is why the consequences are frequently felt most in assets, housing, benefits, and administrative decisions that follow a divorce after 50, especially when retirement security is part of the picture.

References

- Pew Research Center. “8 facts about divorce in the United States” (Oct. 16, 2025).

https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2025/10/16/8-facts-about-divorce-in-the-united-states/

- NCFMR (BGSU). “Gray Divorce Rate in the U.S.: Geographic Variation, 2017” (FP-19-20, 2019).

https://www.bgsu.edu/ncfmr/resources/data/family-profiles/allred-gray-divorce-rate-geo-var-2017-fp-19-20.html PDF: https://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/FP/fp-19-20-gray-divorce-geo-var.pdf

- NCFMR (BGSU). “Age Variation in the Refined Divorce Rate, 1990 & 2023” (FP-25-24).

https://www.bgsu.edu/ncfmr/resources/data/family-profiles/FP-25-24.html PDF: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1379\&context=ncfmr\family\profiles

- NCFMR (BGSU). “Marriage Duration at Time of Gray Divorce, 2022” (FP-24-12).

https://www.bgsu.edu/ncfmr/resources/data/family-profiles/FP-24-12.html

- NCFMR (BGSU). “Multiple Gray Divorces: Demographic Trends & Comparisons” (FP-24-22).

https://www.bgsu.edu/ncfmr/resources/data/family-profiles/FP-24-22.html PDF: https://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/FP/FP-24-22\Multi%20Gray%20Divs\2024-10-09\kkp\cms.pdf

- NCFMR (BGSU). “Divorce Timing and Economic Well-being” (FP-16-01, 2016).

https://www.bgsu.edu/ncfmr/resources/data/family-profiles/spangler-brown-lin-hammersmith-wright-divorce-economic-fp-16-01.html PDF: https://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/FP/spangler-brown-lin-hammersmith-wright-divorce-economic-fp-16-01.pdf

- NCFMR (BGSU). “Marital Status Distribution of U.S. Adults Aged 65 and Older, 1990–2022” (FP-24-04, 2024).

- NCFMR (BGSU). “Long-Term Marriages among Older U.S. Adults, 2022” (FP-24-01, 2024).

https://www.bgsu.edu/ncfmr/resources/data/family-profiles/loo-long-term-marriages-among-older-us-adults-2022-fp-24-01.html PDF: https://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/FP/FP-24-01-Long-Term-Marriages.pdf

- CDC/NCHS. “FastStats: Marriage and Divorce.”

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/marriage-divorce.htm

- CDC/NCHS. “NVSS – Marriages and Divorces (methods & data access).”

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/marriage-divorce.htm

- Social Security Administration. 20 CFR § 404.331 (Divorced spouse’s benefits).

https://www.ssa.gov/OP\Home/cfr20/404/404-0331.htm

- Social Security Administration. “Who can get Survivor benefits” (includes divorced spouse eligibility).

https://www.ssa.gov/survivor/eligibility

- IRS. Publication 504, “Divorced or Separated Individuals.”

PDF: https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p504.pdf Landing page: https://www.irs.gov/publications/p504

- U.S. Department of Labor. “Continuation of Health Coverage (COBRA).”

https://www.dol.gov/general/topic/health-plans/cobra

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. GAO-20-435, “Retirement Security: Older Women Report Facing a Financially Uncertain Future” (July 14, 2020).

PDF: https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-20-435.pdf Product page: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-435

- Brown, Susan L., & Lin, I-Fen. “The Graying of Divorce: A Half Century of Change” (2022).

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9434459/

Information only; not legal advice. Divorce is governed by state law, and timelines and outcomes depend on case facts and local court procedures.

Author Bio

The Marble Team

Your family & immigration law firm

We are Marble - a nationwide law firm focusing on family & immigration law. Marble attracts top-rated, experienced lawyers and equips them with the tools they need to spend their time focused on your case outcome.

See my bio page

Quality legal help for life’s ups and downs

Get started right away

Family Law

Immigration Law

Disclaimer

Attorney Advertising. Prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome. The individuals represented in photographs on this website may not be attorneys or clients, and could be fictional portrayals by actors or models. This website and its content (“Site”) are intended for general informational purposes only. It does not constitute legal advice and is no substitute for consulting a licensed attorney. Only an attorney can provide you with legal advice, only after considering your specific facts and circumstances. You should not act on any information on the Site without first seeking the advice of an attorney. Submitting information via any of the forms on the Site does not create an attorney-client relationship and no such communication will be treated as confidential. Marble accepts clients for its practice areas within the states in which it operates and does not seek to represent clients in jurisdictions where doing so would be unauthorized.

Quality legal care for life’s ups and downs

Our services

Client support

Disclaimer

Legal information